Set One: Ballads; Disc Two; Track Four: "Gonna Die With My Hammer In My Hand" performed by Williamson Brothers and Curry. "Vocal solo with duet chorus with violin and two guitars." Recorded in St. Louis, MO on April 26, 1927. Original issue Okeh 45127 (W80757).

Arnold and Irving Williamson were from Logan County, West Virginia. They recorded six sides for Okeh in 1927 before returning to the obscurity from whence they came. Arnold played fiddle and Irving played guitar. They are joined on this selection by a second guitarist known only as Curry, about whom absolutely nothing is known. Reportedly, the Williamson brothers traveled from their native West Virginia to Saint Louis, Missouri in the company of Frank Hutchison, who appears on the very next selection ("Stackalee"). While the Williamson brothers have always sounded African American to my ears, the available evidence would seem to suggest that they were white, but heavily influenced by African American music. Hutchison (who was white) was apparently a neighbor of theirs, and one would assume that the strict social conventions of the day would have discouraged integrated housing. This is far from conclusive, however. Elvis Presley grew up in integrated neighborhoods in both Tupelo, Mississippi and Memphis, Tennessee during the 1930s and 40s. Poor whites and poor blacks were often forced to live in close proximity, so it may well have been that the Williamsons were African Americans, after all. If anyone has any more conclusive evidence on this matter, please contact me at wheredeadvoicesgather1@gmail.com.

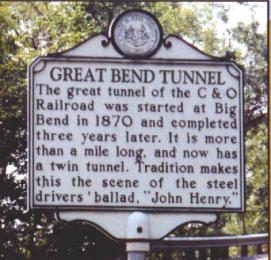

The legend of John Henry is an integral part of American folklore and it is reportedly based on fact. There was a John Henry employed by the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Railway during the 1870s and work was being done at the Big Bend Tunnel near Talcott, West Virginia. There are several scholars who dispute exactly where and under what circumstances the contest with the steam drill actually took place. One theory is that John Henry was a convict leased to the C&O Railway by the State of Virginia. Others maintain that John Henry and the steam drill actually had their race in Alabama. Most sources agree, however, that John Henry was a black man.

All versions of his story depict him as a railroad worker who wields a heavy (usually nine pound) hammer. John Henry is usually a spike driver, which is a man who drives steel spikes into sheer rock in order to dig a tunnel. This was exhausting and dangerous work. Even more dangerous was the profession of the "shaker," whose job it was to hold the steel spike steady while the spike driver drove it in, and then shake it around to loosen the rock. One badly aimed swing could cost the shaker his life. Little wonder, then, that the railroads sought to replace human workers with steam driven machines that could do the work faster and with much less risk. Nevertheless, this advance would cost a lot of men their jobs, and it was for this reason that John Henry sought to prove that human labor could compete with the steam drill.

Whether the race really took place in Virgina, West Virgina, or Alabama - or whether the race really happened at all - the story of John Henry, a man who challenged the technology meant to replace him and won, endures in American popular culture. His story survives in legend and in song. The "John Henry" song - also known as the "hammer" song - exists in countless variants and is arguably the most sung and most recorded folk song in American history. There are two types of "hammer" song. The first is the ballad (of which "Gonna Die With My Hammer In My Hands" is an example), which tells the story of John Henry. The second is exemplified by Mississippi John Hurt's "Spike Driver Blues" (which will be heard in the third volume of the Anthology). This type of song is usually a protest. When John Henry is brought into this type of song, it is as an example of what the singer does not want to become. "This is the hammer that killed John Henry," Mississippi John Hurt sings in "Spike Driver Blues," "But it won't kill me." John Henry is a latter day Christ figure and the hammer is his crucifix. John Henry is martyred for all working men left behind by new technology. Unlike the resigned shoemaker of "Peg and Awl," John Henry attempts to resist, even if he dies in the attempt.

John Henry, he told his captain:

"A man ain't nothin' but a man.

Before I be beaten by this old steam drill,

I'm gonna die with my hammer in my hand.

Lord, lord!

Die with my hammer in my hand."

John Henry, he told his captain:

"Captain, how can it be?

The Big Bend Tunnel on the C&O Road

Is gonna be the death of me.

Lord, lord!

Gonna be the death of me."

John Henry had a little hammer.

Handle was made of bone.

Every he hit the drill on the head

Hammer reaches down and groans.

Lord, lord!

Hammer reaches down and groans.

John Henry, he told his shaker:

"Shaker, you better pray.

For if I miss this six foot steel,

Tomorrow be your burying day.

Lord, lord!

Tomorrow be your burying day."

John Henry had but one only son.

Sat in the palm of your hand.

The very last words John Henry said:

"Son, don't be a steel driving man.

Lord, lord!

Son don't be a steel driving man."

John Henry had a little woman.

Her name was Sally Ann.

John Henry got sick and he could not work.

Sally drove her steel like a man.

Lord, lord!

Sally drove her steel like a man.

The Williamson Brothers and Curry turn in a whirlwind of a performance on this record. The fiddle and two guitars blaze through the instrumental passages. Their reading of John Henry's story is not particularly coherent. The verses are tossed off, almost as an afterthought. They never even get to the race with the steam drill. Instead, a series of vignettes are described: John Henry addressing his captain; a description of his hammer and its bone handle; John Henry's final advice to his son; and a description of John Henry's "little woman," Sally Ann. No story is actually told in this song, not that it particularly matters. The Williamson Brothers and Curry churn the song out at breakneck speed, almost as though they were racing for their lives.

Here and in the previous song, Smith juxtaposes two songs about black railroad workers associated with West Virgina, both named John. Both men go to their deaths bravely, both men address their final words to their children. Indeed, there was often confusion between the two, and some have even claimed that they were the same person. The Williamson Brothers and Curry with their wild instrumental performance and spirited choruses - punctuated with cries of "Lord, lord!" - are a marked contrast with Sara Carter's deadpan account of John Hardy's deeds.

The Wrath of the Shameless Plug Department: Check out the third episode of the "Where Dead Voices Gather" podcast. This week's episode is a special program of holiday music, featuring performances by Bessie Smith, Count Basie, Charles Brown, and Fiddlin' John Carson, as well as Christmas music from Trinidad, the Ukraine and Puerto Rico. Also available on iTunes. Subscribe now so you don't miss a single episode!

You can also become a fan of "Where Dead Voices Gather" on Facebook and follow us on Twitter. Where Dead Voices Gather: Using today's technology to promote yesterday's music!

Bruce Springsteen captures a good deal of the wildness of the Williamson Brothers and Curry in this live performance of "John Henry" recorded while he was promoting his album, The Seeger Sessions.

A completely different version of the John Henry legend, rich in detail, is performed Johnny Cash during a episode of his 1969-1970 television series.

Download and listen to the Williamson Brothers and Curry - "Gonna Die With My Hammer In My Hand"

Pals and I are a part-time porch punk band and this is the only song we know (well). We think it reveals a lot about the American work ethic, you know? Or sometimes the lack thereof.

ReplyDeleteThis is a hell of a blog, by the way. If I know how blogs worked, I'd totally 'follow' it.

Like I said above: John Henry is an American mythological figure. The American version of Prometheus (or Jesus). He can and does mean a great many things. A symbol of the American work ethic (albeit one dragged to America in chains) is just one of many meanings his story holds for us.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the kind words. I hope to start blogging more regularly in the near future, so you might have something to "follow."

Ervin Williamson was my late father in law, I never met him, he died in 1971, he was a white man born in Wayne County WV then settled in Logan, WV with his brothers. I am married to Ervin’s son, Raymond and our son Brayden Williamson, who is 22 years old, is carrying on the tradition of bluegrass and gospel music, as well as other genre’s. Look my son up on YouTube. He is very musically talented, like his grandfather. You can find more on Ervin and his brother on the PBS series American Epic. You can contact me with more information at teresaw25601@gmail.com

ReplyDelete